10-Year Lows vs 40-Year Highs Who’s Mispriced? The Case For The Commodity Comeback

Repricing scarcity: underbuilt supply meets relentless demand

Hey guys,

Today I'm sharing a post from my friend Polymath Investor about the comeback of commodities. Are we facing another super cycle?

Let’s see.

— WorldlyInvest

Ok, let’s start with some facts.

The last major U.S. oil discovery happened when your iPhone didn't exist.

The last approved US copper smelter project dates to 1971 and was never built.

Yet every Tesla rolling off the assembly line devours 180 pounds of copper, every data center housing ChatGPT uses tons of the red metal, and that cool MacBook contains traces of 30 different minerals nobody thinks about.

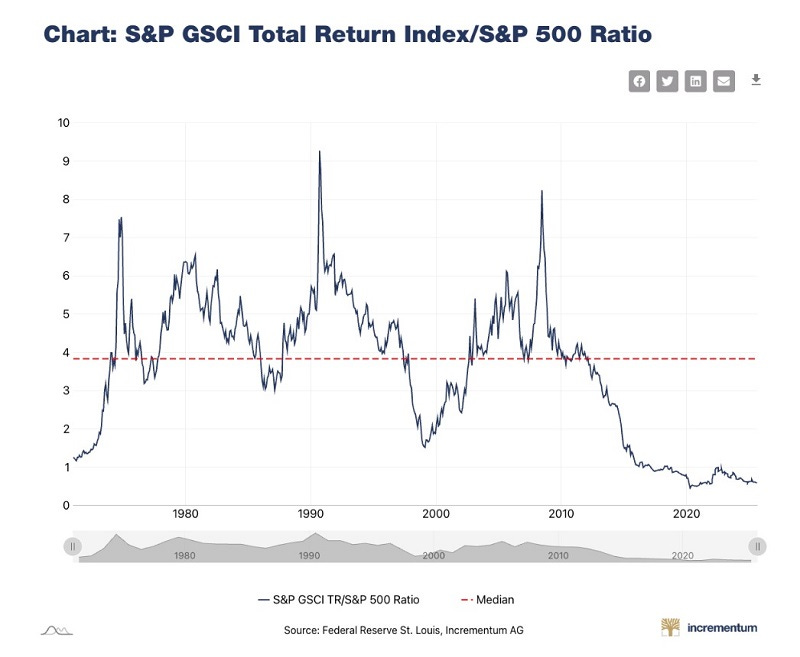

This is the investment paradox for 2025: while high flying tech stocks trade at sky high multiples, the physical materials enabling our digital future trade at 50-year lows relative to the S&P 500, a disparity not seen since Nixon abandoned the gold standard in 1971, right before commodities embarked on one of their greatest bull run in history.

This chart shows how cheap or expensive commodities (like oil, metals, and crops) have been compared to the stock market since the early 1970s. When the line goes up, commodities are expensive compared to stocks, like during the oil crisis in the 1970s, the Gulf War in 1990, and the 2008 financial crisis. When the line drops, commodities are cheap compared to stocks, like in the early 1970s, the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, and the early 2020s.

The Physics of Scarcity Meets the Psychology of Neglect

Consider the chart above. The market is pricing (relatively) commodities as if supply were infinite and demand was dying.

Why is everyone apparently ignoring these numbers?

Behavioral finance could offer an answer: recency bias has trained an entire generation to believe tech stocks only go up while commodities only disappoint. The typical portfolio manager is scarred by commodity underperformance from 2011-2020.

Nevertheless, the physics of depletion adds urgency to this mispricing. Unlike software that scales infinitely with near-zero marginal cost, every barrel of oil burned is gone forever, every pound of copper mined increases the entropy of the remaining deposits.

“Over the last 30 years, there’s been a decrease of approximately 35% in average copper grades. Ore mined today typically contains 1% or less copper, in contrast to 150 years ago when ore grades typically exceeded 5%. This reduction in ore grade increases mining and processing costs.” [1]

So, can technology overcome the Second Law of Thermodynamics?

Dancing on the Volcano of Underinvestment

You might argue we still have time and that, if demand is there, investment will follow. Not so fast. A new copper mine typically takes 23 to 24 years from discovery to first production and costs billions. Other minerals aren’t much quicker: nickel mines average around 17.5 years, gold mines typically take 15 to 16 years, and even lithium greenfield projects (especially brine-based) can stretch up to 10 years before reaching production.

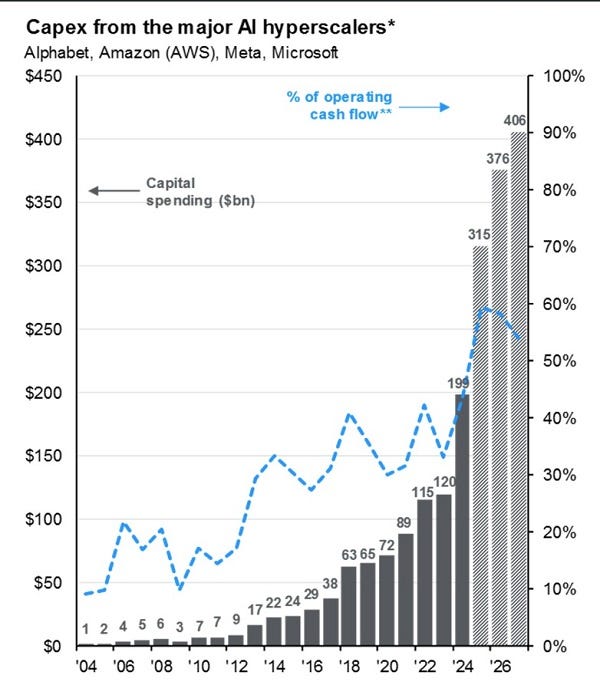

The capital that could have funded these projects in recent years has instead chased quick mark-ups in software valuations.

Apparently, and according to some estimations, the mining and metals industry will need to invest US$1.7 trillion over the next 15 years for enough supply of copper, cobalt, nickel and other critical metals[2], yet capital expenditure among the 30 largest miners actually fell 1.8% in 2024.

This chronic underinvestment has created a supply time bomb: copper faces an 8.9 million tonne deficit by 2030[3], lithium markets project a 700,000 tonne shortfall[4], and London Metal Exchange inventories sit at 25-year lows[5].

And it doesn’t stop there.

The energy transition dramatically amplifies this supply crisis.

A single wind turbine requires 300 tons of steel and 5 tons of copper. Electric vehicles need six times more minerals than conventional cars.

The International Energy Agency projects clean energy mineral demand will grow sevenfold in aggressive decarbonization scenarios, yet exploration spending plateaued in 2024 after years of minimal growth.[6]

So, where will these materials come from when it takes a decade or two to build new capacity?

History rhymes with eerie precision here.

The last time commodities traded at such extreme discounts to equities—1971—gold subsequently returned 40% annually through the decade while the S&P 500 went nowhere in real terms.

Are we watching the same movie with different actors?

Maybe.

Of course, commodities are a mix bag and we will see different scenarios play out in different sectors.

In the case of gold though, the rally already started and the conditions are favourable for more tailwinds.

When Inflation Makes Boring Beautiful

Central banks globally are cutting rates in 2025 even as inflation may prove stickier than expected, the Federal Reserve anticipates there may be two more cuts before pausing, while the European Central Bank continues gradual easing.

This monetary cocktail historically favors commodities.

According to Goldman Sachs,

"A 1 percentage point surprise increase in US inflation has, on average, led to a real (inflation adjusted) return gain of 7 percentage points for commodities, while that same trigger caused stocks and bonds to decline 3 and 4 percentage points, respectively".[7]

During five major inflationary periods over 50 years (1970s oil embargo, Iranian Revolution, China's boom periods, post-pandemic recovery), commodities outperformed equities and bonds across all episodes. [8]

You can start getting the picture, the breadcrumbs are there.

Sentiment indicators show retail investor interest in commodity, and more so in energy, is in multi-year lows, which is of course a powerful contrarian signal.

Meanwhile, MIT research reveals 95% of organizations are getting zero return on their generative AI investments[9], yet tech valuations price in revolutionary productivity gains and hyperscales keep a breakneck pace of investment.

I know, it might still be early and there are already a lot of tangible benefits in sectors like software development, drug discovery or customer service automation. We will have to see how the story evolves.

Professor Damodaran often reminds us that effective valuation requires both quantitative analysis and compelling narratives. AI companies clearly have their story, and now commodity producers are beginning to shape theirs. That makes me ask the question: which of these narratives has more fragile assumptions?

Closing Reflection

The copper mine that hasn't been built, the oil field that hasn't been drilled, the lithium deposit that hasn't been developed, these absent investments from the past decade will define the next one.

While hyper-scalers mesmerize investors with artificial intelligence promises, the physical world reasserts its primacy through scarcity, depletion, and thermodynamic reality.

The greatest fortunes in the next decade won't come from the next social media app but from owning the irreplaceable materials that make modern civilization possible.

As the commodity cycle turns once more, perhaps the most radical investment act in 2025 is simply remembering that the digital economy floats on an ocean of very physical, very finite, increasingly scarce materials, materials that patient investors can buy today at prices that discount the very limits of nature.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to Polymath Investor—a newsletter where I explore investing through an interdisciplinary lens and dive deep into overlooked small caps from around the world.

— Polymath Investor

[1] Horizon Copper. (2024). Why copper. Horizon Copper. Retrieved September 18, 2025, from https://www.horizoncopper.com/why-copper/

[2] EY. (2022, April 25). Critical minerals supply and demand challenges mining companies face. https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/energy-resources/critical-minerals-supply-and-demand-issues

[3] Discovery Alert. (2025, February 19). Copper production, capital allocation, and the mining investment gap in 2025. Discovery Alert. https://discoveryalert.com.au/news/copper-production-capital-allocation-mining-2025/

[4] EY. (2022, April 25). Critical minerals supply and demand challenges mining companies face. https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/energy-resources/critical-minerals-supply-and-demand-issues

[5] Investing News Network. (2024, December 27). Copper squeeze: What low LME inventories mean for the market. Investing News. https://investingnews.com/copper-squeeze-lme-inventories/

[6] D’Orazio, P. (2024). Assessing the fiscal implications of changes in critical minerals’ demand in the low-carbon energy transition. Applied Energy, 376, 124197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124197

[7] Struyven, D., & Thomas, L. (2024, June 25). Which commodities are the best hedge for inflation? Goldman Sachs Research. Retrieved September 18, 2025, from https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/which-commodities-are-the-best-hedge-for-inflation

[8] Struyven, D., & Thomas, L. (2024, June 25). Which commodities are the best hedge for inflation? Goldman Sachs Research. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/which-commodities-are-the-best-hedge-for-inflation

[9] MIT study on AI profits rattles tech investors. (2025, August 21). Axios. https://www.axios.com/2025/08/21/ai-wall-street-big-tech

Mauricio (aka Polymath Investor) does it again. Excellent post my friend.

While the post was high level and looked at commodity values collectively relative to equities, other than copper which has been a firm favourite of commodity traders for a couple of years now due to AI and tech developments generally, which commodities do you think are still flying under the radar of most investors?

I explored Platinum recently: https://rockandturner.substack.com/p/part-2-capital-cycle-opportunity . This looks ridiculously undervalued relative to gold.

Are there any others?

The problem is that some of us have been patiently investing towards this for the last some years, and it has been of course been difficult!